This blog tells the story of one family, or rather a network of connected families, living in London in the seventeenth- and eighteenth-centuries. Those families are my ancestors. I began by telling the story of one of the families, the Bynes, several of whom moved from rural Sussex to the city in the middle of the seventeenth century. One of them, John Byne, was was my 8 x great grandfather; he was a stationer at Tower Hill. His daughter Mary married goldsmith Joseph Greene in 1702, and in the last two posts I’ve traced Joseph’s roots in the riverside hamlet of Ratcliffe, in the parish of Stepney in what is now London’s East End. The last post summarised what I’ve been able to discover about Joseph’s father, Captain William Greene, a mariner and Warden of Trinity House during the brief reign of James II.

In this post, I want to tell Joseph’s own story. He was born in Ratcliffe on or about 20th February 1677/8, to William Greene and his second wife Elizabeth, who had married in the previous year. Joseph was baptised at the parish church of St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney, on 14th March 1677/8. We know nothing about his childhood, except for the fact that his father William died early in 1686, when Joseph would have been eight or nine years old. In his will, Captain Greene left his son ‘all my silver plate gold rings and jewells whatsoever’. Joseph was also granted ‘the house I now live in and all the interest and terme of years that I have therein and yet to come and unexpired after the death of his mother my said wife Elizabeth Greene’. Finally, William bequeathed Joseph ‘all my debts and moneys whatsoever to me due and owing by bills bonds … or otherwise’.

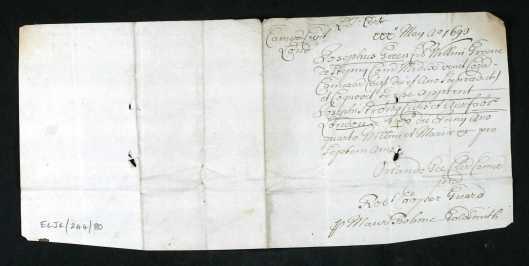

Joseph Greene’s apprenticeship certificate

The next record we have for Joseph dates from 15th June 1692, when he would have been fourteen years old. It was on this date that he was apprenticed to Joseph Strong, citizen and goldsmith of St Catherine’s Street, which ran alongside the Thames in the parish of St Katharine’s by the Tower. The signatories on the apprenticeship certificate, issued in the following May, include Sir Orlando Gee, who was steward to the Earl of Northumberland and Registrar to the Court of Admiralty, and Maurice Bohme or Boheme, another goldsmith.

Joseph Strong, Joseph Greene’s apprentice master, had married Elizabeth Wyard at St Katherine’s church in 1676. They had four children: Ephraim, born in 1680; Elizabeth in 1683; Joseph junior in 1685; and Hannah or Anna in 1690. Joseph Strong’s daughter Elizabeth married William Harris, a clockmaker and constable of the assize in Maidstone, Kent. The Harris family, who included goldsmiths as well as clock and watch makers among their number, were closely associated with the Earl Street Presbyterian Chapel in Maidstone, whose pulpit would later be occupied by the father of William Hazlitt, and there is some evidence that the Strong family were also Dissenters. The fact that Joseph Strong gave his son and heir the Old Testament name Ephraim is something of a clue, as is Strong’s will of 1707, in which he commits his soul ‘into the hands of Almighty God my Creator hopeing through the alone merits of Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ to obtaine a full remission of all my transgressions and to be received into those mansions of bliss which he hath purchased and prepared for all true believers’.

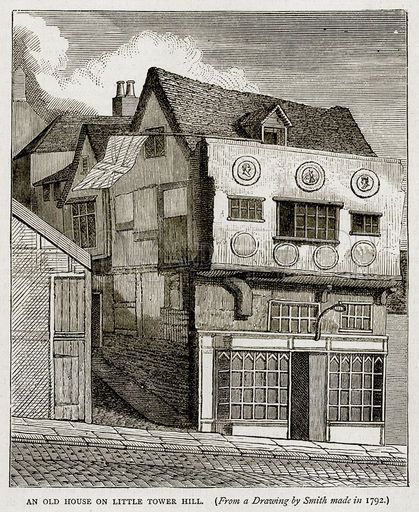

The full name of the church where members of the Strong family were christened, married and buried was the Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katharine by the Tower. A medieval foundation close to the Tower of London, it was unusual in not being dissolved at the Reformation, since it was personally owned and protected by the Queen Mother. It was re-established in Protestant form and grew to be a village offering sanctuary to immigrants and the poor, and consisting of over a thousand houses, crammed into narrow lanes. St Katharine’s survived the various religious upheavals of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and even hostility from extreme Protestants during the Gordon riots of 1780, but was completely demolished in 1825 to make way for the St Katherine Dock.

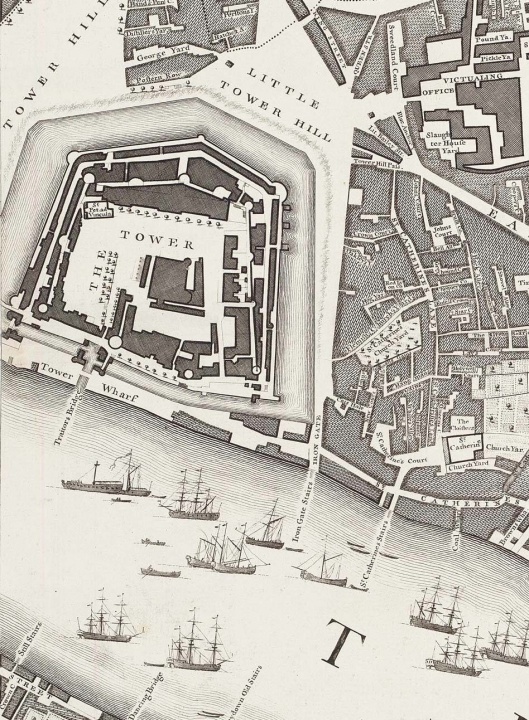

Little Tower Hill on Rocque’s London map of 1746

Joseph Strong’s house and workshop would have been only a short distance from the corner of Little Tower Hill and the Minories, where his apprentice Joseph Greene would eventually set up his own goldsmith’s shop. There is some confusion over when Joseph Greene was ‘made free’. I always believed that apprentices were unable to marry until they obtained their freedom. However, the extant records declare that Joseph became a freeman on 14th April 1708 and a liveryman in October of the same year. However, this would have been a full six years after his marriage to Mary Byne.

That marriage took place on 19th March 1701/2 at the church of All Hallows London Wall, when Joseph was twenty-four years old and Mary eighteen. If Joseph had already set himself up in business at Tower Hill when the couple met, then the Bynes would have been his neighbours. Alternatively, if Joseph was still an apprentice in nearby St Catherine’s Street, it’s possible that the couple moved to Tower Hill after their marriage, in order to be close to Mary’s family.

On 16th October 1703 Joseph and Mary Byne had a son, also named Joseph, baptised at the church of St Botolph, Aldgate. Two years later, on 20th December 1705, their daughter Anne was christened, but she died three days later. The Greenes would have two more children: Mary, born in 1702, and Elizabeth in 1711.

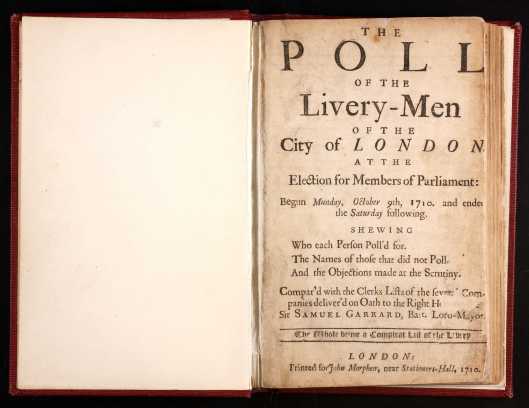

In 1708 Joseph took on his first apprentice, Francis Robert, and in 1713 a second young man, Giles Bond, was apprenticed to him. Joseph Greene voted in the General Election of October 1710, his votes being recorded in the poll book of the Liverymen of the City of London. Eight candidates stood for election in London: Sir Gilbert Heathcote, Sir William Ashurst, Sir James Bateman and John Ward for the Whigs, and Sir William Withers, Sir Richard Hoare, Sir George Newland and Sir John Cass for the Tories. Joseph cast his four votes for the Tory candidates, all of whom were victorious. In fact, they were part of a national Tory landslide in an election that was as much about religion as politics.

In the following year, Joseph Greene took out an insurance policy on his house with the recently-established Sun Fire Office, the record declaring that Joseph Green, citizen and goldsmith, was resident at the sign of the Golden Ball and Ring at the corner of Little Tower Hill, next to the Minories in the parish of St Boltoph, Aldgate. Other trade records confirm that Joseph would continue to live and work at the same address until at least 1734. Interestingly, some of these records describe Joseph as a pawnbroker as well as a goldsmith.

In her fascinating book about Charles II, Jenny Uglow writes about the king’s financial problems and his indebtedness to a new breed of bankers that sprang up in London around this time (my emphasis):

Some of the new bankers were former scriveners, notaries who negotiated loans and then began lending their own capital. But by far the most influential were the London goldsmiths. For a century or more, the goldsmiths had sold fine silver and gold plate to the nobility and gentry, agreeing to take it back a security against loans when times were hard. From pawn-broking they moved to full-scale banking. People deposited cash with them, receiving a low rate of interest, and the goldsmiths lent it out again at a higher rate, set by law at six per cent.

[…]

[The London goldsmiths] not only gave interest on deposits, but also discounted bills of exchange, accepted the new-fangled cheques, first issued in 1659, and issued ‘goldsmiths notes’, promissory notes that could change hands and circulate freely, creating a fluid movement of capital. They also lent to each other, helping each other out when exceptionally large sums were needed or when the cash-flow failed, and they kept careful tallies so that they knew how exposed they were, every week, every day and even, in some crises, every hour.

Joseph and Mary Greene lost two of their children in early adulthood. On 27th August 1725 their daughter Elizabeth was buried at St Botolph’s; she was eighteen years old. Three years later, on 13th October 1728, their son Joseph was laid to rest at the age of twenty-five. The causes of their deaths are unknown, nor have I been able to discover whether Joseph junior had already married, or what his profession was, though I assume he was intended to inherit his father’s business.

In the General Election of 1727, which was triggered by the death of George I, Joseph Greene’s voting behaviour was a little less uniform than it had been seventeen yeasrs earlier. In fact, he split his allegiance between the two main parties, voting for Micajah Perry and John Barnard, who were Whigs, and for Humphrey Parsons and Richard Lockwood, who were both Tories. Perry, Parsons and Barnard were all elected, together with Sir John Eyles, another Whig.

On 8th July 1729 Joseph and Mary Greene’s only surviving child, Mary, was married at All Hallows, London Wall, the church where her parents had married twenty-seven years earlier. The bride was nineteen years old and the groom, John Gibson, was somewhat older at thirty. Little is known about Gibson’s origins, but his intriguing life story will be the subject of a later post in this series.

John and Mary Gibson were my 6 x great grandparents. They would produce four daughters, Jane, Frances, Anne, and my 5 x great grandmother Elizabeth, before the death of Mary’s father Joseph Greene in 1737. All four were born at Tower Hill, and there is evidence that Elizabeth, at least, was born in her grandparents’ house on the corner of Little Tower Hill and the Minories.

Joseph Greene made his will on 6th February 1736/7. It is brief and to the point, concerned mainly with financial matters, and it contains few clues about his family or friends. One of the witnesses, Joseph Letch, seems to have been a lawyer at the Middle Temple, and was probably the family attorney. The main business of the will was to ensure that Joseph’s only surviving daughter Mary received the generous amount of money promised in her marriage settlement. Mary had been promised £2000 and is now bequeathed a further £1000: this would be equivalent to about £250,000 (or $370,000 US dollars) in today’s currency.

In other words, Joseph Greene was a wealthy man by the time he died, on 26th December 1737. Not only was he able to bequeath a sizeable sum of money to his only surviving child, but he also left sufficient funds to enable his widow to purchase a country estate which she then transferred to the ownership her daughter and son-in-law. But the story of the varying fortunes of John and Mary Gibson will have to wait until a later post.

Fascinating pieces of history here Martin. I find it interesting where you refer to the goldsmiths as being the early bankers and will pursue the Jenny Uglow “A Gambling Man” out of my further interest in financial matters.

It seemed quite busy in those early years of the Greens. I’m grateful you are able to sort through the history. The Captain William Greene is still resonating with me.

Life as a goldsmith must have been quite prestigious and carried with it a great burden of financial equity.

Your next instalment is equally highly anticipated.

nb: Elizabeth G (your 5xgg) is my 4xgg ( I think this is correct)

LikeLike

Thank you. I hope you enjoy ‘A Gambling Man’ – I certainly did.

I’m afraid you’ll have to wait a while for the story of Elizabeth Gibson. There’s her father’s fascinating to story to tell first.

But even before that, I’ll be making a rather big detour to write about the Forrest family – watch this space.

LikeLiked by 1 person